Many people feel disappointed by the Rucho v. Common Cause decision, handed down last week by the Supreme Court. I don’t blame them. The Supreme Court recognized that partisan gerrymandering is, in their own words, “incompatible with democratic principles”, yet refused to do anything about it, finding it non-justiciable — meaning outside the purview of the Court to overrule. “Federal judges,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts, “have no license to reallocate political power between the two major political parties, with no plausible grant of authority in the Constitution, and no legal standards to limit and direct their decisions.”

But if the Supreme Court cannot strike down blatantly partisan gerrymanders, who can? Is there any hope of having fairly drawn districts, where voters can have meaningful choices on the question of who will represent them? The Court hopes the issue can be addressed by state courts and by the political process within the states. But state courts don’t have a great track record of protecting the political rights of their citizens.

Reformers are placing their hopes in independent redistricting commissions, in which a politically balanced group of non-politicians decide on the maps to be used for electoral districts. For example, Arizona passed a law in 2000 setting up a commission of two Democrats, two Republicans, and one independent chair, drawn from citizens who have not, within the preceding three years, held public office (except for school boards) or “served as a registered paid lobbyist or as an officer of a candidate’s campaign committee”.1 Other states, including California, Idaho, New Jersey, and Washington, also use independent commissions for redistricting.

But this approach seems a bit like a band-aid. It relies on the judgment of a small number of individuals, who are not directly accountable to voters. There’s a chance that our now more conservative Supreme Court may strike down the use of these commissions at some point in the future.2

Furthermore, disproportionality of party representation is not the only problem with gerrymandering. It can also be used to protect incumbents, of both parties — something a bipartisan commission may be very happy to support. In the case of a 2001 California redistricting proposal, for example, Democrats opted against an “aggressive” reapportionment plan in favor of one that would make their party’s elected representatives more secure in their seats. “Our objective,” said the state party chairman, “has been to create stronger Democratic seats.”3 Far from promoting accountability through competitive districts, such incumbent-favoring arrangements help create “a series of one-party fiefdoms in which a single party rules and voters feel helpless to change it.”4

There is another approach that would promote competitive elections while drastically reducing the possibilities for gerrymandering: proportional representation (PR) using multi-member districts.

Single-member districts are winner-take-all districts. A political party wins either one seat or none — all or nothing. By contrast, with multi-member districts we can give seats to more than one party, in proportion to how many votes they get. Because districts are not all-or-nothing battles, there’s less incentive for gerrymandering — and less scope.

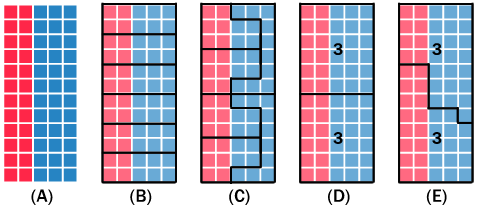

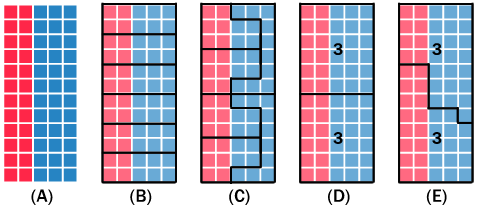

Consider the diagram below, showing a hypothetical electorate of 60 voters (A), to be represented by six elected officials, where 24 of them (40 percent) belong to the “red” party and 36 (60 percent) belong to the “blue” party. On the left, in (B) and (C), we assume single-member districts, with ten voters per district. By putting the same number of each type of voter into each district (as shown in B), we can rig things so that red gets zero representation. On the other hand, by carefully “packing” blue voters into two all-blue districts, we can ensure that they will only win those, resulting in a total of four red representatives and two blue — even though blue voters outnumber red. Both results are way out of proportion.

But now suppose we divide the electorate into only two districts, of 30 voters per district, with each electing three representatives. (For the sake of simplicity, I’ll assume party-list PR, using the D’Hondt method of allocating seats, although the single transferable vote might actually be a better option.) In the simplest geographical division, shown in (D), each district has 12 red voters and 18 blue. And each would elect one red and two blue representatives, for a total of two red and four blue. That’s two-thirds of the seats for one party and one-third for the other — not exactly proportional to the 60-40 split of the electorate, but not too far off.

If you’re a partisan map-drawer, you’ll have a harder time manipulating these multi-member districts for the benefit of your party. For one thing, there’s no way to completely deprive the other party of representation. “Packing” and “cracking” don’t work so well when seats are allocated proportionally.

If you’re a consultant for the blue party, there’s no way to redraw the map to get more than the four seats you get in (D), where you’re already getting more than your fair share. Red is only getting one rep in each district. If you move enough of those red voters from one district to the other to eliminate their seat in the one, you will only add to their seats in the other.

If you’re a consultant for the red party, there is a way (E) for you to get more seats—three instead of just two, a 50-50 split instead of two-thirds to one-third. But that’s the best you’ll be able to do. And this fact is partly because we’re supposing such a small number of representatives per district. A system that has five or more seats in every district is “effectively immune from gerrymandering.”5

Aside from making gerrymandering impractical and unprofitable, multi-member districts with proportional representation would also allow for much more accurate representation of the varied interests of the people. That’s why they’d be a much more permanent, stable solution to the problem than independent redistricting commissions. Lawmakers can create commissions, and they can also dissolve them, when people get complacent or when incentives or political calculations change. But PR might be politically harder to revoke once well-established, because it’s better for voters in so many ways.

There’s one more reason for switching from single-member districts to multi-member. It would allow us to pursue the goal of racial integration without worrying about racial minorities losing representation. See, when a racial or ethnic minority group is geographically concentrated, we can ensure their representation under single-member-district conditions by drawing a “majority-minority” district, which means packing them into a district where they have enough votes to elect someone of their choice. But if they were geographically integrated with members of other races or ethnicities, it would not be possible to draw a single-member district that fulfills this purpose. So the goals of minority representation and racial integration are in conflict.

But this conflict only exists because of single-member districts. Multi-member districts avoid it, by allowing minorities to be represented proportionally within each district — and not just racial or ethnic minorities, but any kind of minority, political, religious, or otherwise.

It’s time to rethink some of our basic assumptions about districting. Multi-member districts were commonly used in American history, though not with proportional representation. We should consider trying them again, this time with proportionality. By doing so, we can give our democracy a major upgrade, and make gerrymandering a thing of the past.

Notes:

- See https://www.azleg.gov/const/4/1.p2.htm

- For example, Chief Justice John Roberts, dissenting in Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona. Independent Redistricting Commission (2015), argued that the people had no authority to create an independent redistricting commission, because the Constitution says that electoral matters “shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof”.

- John Wildermuth, “Lawmakers use creative license in redistricting: Oddly shaped congressional maps would largely benefit incumbents”, San Francisco Chronicle, Sept. 2, 2001, p. A6.

- Douglas J. Amy, Real Choices/New Voices: How Proportional Representation Elections Could Revitalize American Democracy, second edition, 2002, Columbia University Press, p. 60.

- Amy, p. 66, with reference to Arend Lijphart and Bernard Grofman, Choosing an Electoral System: Issues and Alternatives, 1984, Praeger (p. 7).