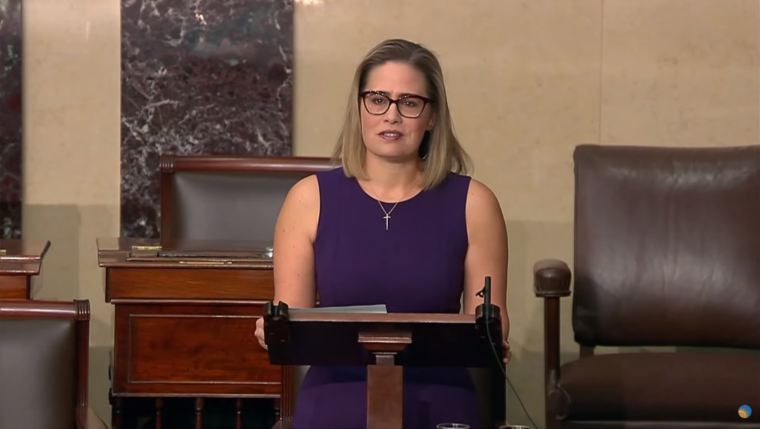

Yesterday, Senator Kyrsten Sinema (D-Arizona) caused a lot of heads to spin when she announced that she would not support altering the filibuster in order to pass voting rights legislation. One prominent columnist tweeted that she was “effectively asking the authors of Jim Crow and vote-rigging to give their permission for her to stop it. This is worse than incoherent or cowardice. It’s a moral disgrace.”

But is it really so hard to see the coherent principles underpinning her position? She views the filibuster as a tool whose value depends on how it’s utilized, and has pointed out that abandoning it now, when Democrats have a narrow majority, could well come back to haunt them when Republicans gain control in the future. In other words, she sees it as a classic example of short-term benefits versus long-term harms.

I’m not going to take a position here on whether the Senate rules should change. But I do want to point out a connection between the structure of our party system and why many people see the filibuster as an important tool.

Majority rule is the fairest way to make collective decisions on sub-constitutional matters. The Constitution provides for only a few cases in which a supermajority is required — such as overriding a presidential veto or amending the Constitution. The filibuster was not part of our original constitutional design. So, on its face, the 60-vote threshold in the Senate seems undemocratic, unnecessary, and obstructionist. But the Framers also never envisioned party control of the Senate (or House).

In our duopolistic party system, only two parties have any realistic chance to win seats. The diversity of interests in the electorate is flattened into just two parties, who both then act as if everyone who voted for them supports their full agenda, when in fact that isn’t true. Many voters cast their ballot based on a single issue — and in many cases, they vote the way they do mainly to make sure the other party doesn’t gain power.

Because there are only two parties, one will always sit in the majority in each chamber, House and Senate. But this is not a representative majority. It doesn’t mean that whatever that party aims to do reflects the will of the majority of voters. It’s an artificially constructed majority that reflects the structure of our party system, the flattening of choices that severely limits voter expression.

The Framers never would have imagined that a single political party could rule on its own. They expected the House and Senate to deliberate and to reach decisions after hearing from different sides on each issue. A system of government by one faction alone is prone to what I call hijacking — taking policy in a direction that doesn’t represent the will of the people.

Lani Guinier wrote in her 1994 book The Tyranny of the Majority, “The conventional case for the fairness of majority rule is that it is not really the rule of a fixed group—The Majority—on all issues; instead it is the rule of shifting majorities, as the losers at one time or on one issue join with others and become part of the governing coalition at another time or on another issue. The result will be a fair system of mutually beneficial cooperation.”

In a multiparty system, such shifting majorities would come a lot more naturally, because no single party would control a majority of seats on its own, except in extraordinary circumstances in which it truly commanded the support of a majority of voters. At least, it would no longer be a norm to have single-party control. The American people are too diverse to be squeezed into just two parties under a more rational system, where parties would more accurately channel public opinion.

In a healthy multiparty system, achieving a majority across party lines would mean a more durable and representative reflection of the public interest. It would mean less chance of what Senator Sinema called “wild reversals of federal policy” when the allocation of seats changes after an election.

Thus, without the norm of a single party controlling the chamber, people would have less to fear from policymaking on the basis of a bare majority, because a bare majority would be far less likely to be an unrepresentative one. And thus, the perceived need for a 60-vote threshold would fade away.

Defenders of the 60-vote threshold often cite bipartisanship as a justification. They may do so for cynical reasons, at times, but the need for policymaking to be representative of a majority is real. Another way to say it is that the 60-vote threshold works to prevent hijacking. At the same time, it often obstructs good policymaking. It’s a clumsy way to accomplish something we need, which comes with collateral damage.

A multiparty system would do more to prevent both hijacking and obstructionism.

I’d say that, both in the way Mitch McConnell deploys it and in most of its historical use, the filibuster has exactly been a way for the minority party to hijack the legislative process. By effectively requiring a supermajority to pass *any* legislation that they don’t like, those acting in bad faith are successfully preventing any progress by the majority party.

Two other points worth noting:

• The 50 Democratic senators represent 43 million more people than the 50 Republican senators do. Because of the 60-vote requirement to pass most legislation, 41 Republican senators representing just 21 percent of the country can block a bill from moving forward.

• If/when the Republicans regain control of the Senate, they won’t hesitate to reform the filibuster when it suits them.